Early 20th Century Housing: Council Housing From The Interwar Period

-

by Trevor Yorke

Trevor Yorke is an experienced author and artist who specialises in period architecture. For more information and to see a selection of his books you can visit his website, here.

There are very few positives which can be written about the First World War. However, the loss of life in the conflict, across all social classes caused a great social change in the following decades and had a marked effect on housing in Britain.

When the whistle to attack sounded it was young officers, often from the upper classes, who led the way out of the trenches and were the first to be cut down by machine gun fire. The loss of the family heir coupled with crippling taxes and the effects of agricultural depression resulted in large numbers of country estates being sold off in the interwar years, providing cheap land for housing.

At the same time, the atrocious conditions the working classes had to live in were highlighted by the poor health of recruits during the later stages of the war and with the Russian Revolution fresh in the mind of the Government it was recognised that more spacious and healthy housing would have to be provided.

Financial schemes which encouraged local authorities to build the first large-scale council estates and the middle classes to buy new houses kick-started the slow, raising of standards of accommodation and created a new obsession with property ownership.

With the low cost of suburban land compared with that in city centres, builders could afford to provide less densely packed housing, hence the new large semis set in spacious front and rear gardens became the standard design during these inter-war years.

There were a wide variety of styles available which could be employed by simply adding a few appropriate details or cladding to the basic form of a semi-detached house.

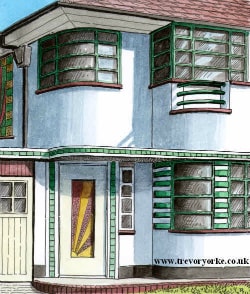

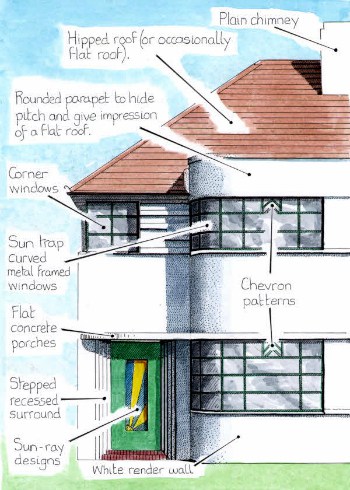

In the 1920s Mock Tudor timber framing, Arts and Crafts pebbledash or Neo Georgian windows were added and then, in the 1930s, modern, streamlined features such as white, rendered walls and Art Deco glazing were added to the mix.

Developers also set their houses along curving crescents or short cul-de-sacs rather than the straight roads which dominated pre-war housing. They also added green spaces and trees to bring the country into the town.

Features which distinguish houses from the 1920s and 30s include:

- Hipped roofs which slope down on all sides became standard on all but the cheapest housing. They were also relatively steep-sided so they make a large space suitable for conversion to make further room. (Although the sloping end may be best replaced by building the side wall up to form a gable to maximise headroom.)

- The semi-detached house was the most common form of housing but the front doors were usually set at the far end of each pair and not in the centre, as had been the norm in pre-war housing types.

- Large, bowed, bay windows with gables decorated with mock timber framing was a popular addition at the front. For the latest in fashion, suntrap bays with a curved side and horizontal glazing bars, usually in metal, was an option in the 1930s.

- Casement windows with the upper section filled with patterned, coloured glass were popular. In traditionally-styled houses, these tend to be colourful floral designs and in Mock Tudor houses, heraldic symbols were popular. In the 1930s geometric patterns like the sunray were popular, either in bold colours or in different textures of clear glass.

- The wall surface could be rendered all over and painted to imitate modern concrete houses, have just the upper storey covered in pebbledash reflecting the Arts and Crafts style or could be clad with imitation timber framing to create a Mock Tudor look. By the 1930s it was fashionable for any exposed bricks to have a wavy or ripple effect pattern stamped in their surface.

- Front doors were either set beneath a simple, flat, storm porch or set back behind an arch with a small window on one or both sides. The door, usually, had a glazed upper-third in a variety of shapes, with the reflective glass installed in the tops of the main windows. Tudor style houses had solid wood doors with vertical battens and sometimes a tiny window at the top. Art Deco style houses usually had a more daring design with a series of glazed horizontal panels stacked above each other, although, more often, they just had a conventional door with geometric, patterned glass.

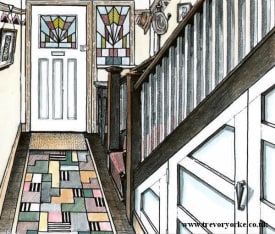

- Inside the extra width of these interwar suburban plots was most obvious in the entrance hall which was now much wider than in most Edwardian houses of a similar class. This meant that the stairs could be brought to the front with wooden balusters providing a decorative feature to boast about. The windows in the hall replaced the fanlight in pre-war houses as the ceiling heights were now generally lower. Kitchens were now built into the main body of the house rather than being in an extension at the rear.

These practical, interwar houses, generally set on spacious plots, have both a style which is gaining popularity and a practical form, needing little adaptation for modern living.

They were usually built with a quality of materials which was superior to those used since the Second World War and included features, like cavity walls and damp proof courses, which make them a safer investment than much of the pre First World War housing.

There are however some areas to look out for when considering Early 20th Century housing for investment:

- Check that the roof looks sound and there are no signs of sagging. Problems can occur with these large hipped structures when the original ceramic roof tiles have been replaced with modern concrete, adding extra weight. Other problems can come from the timber supports, running side-to-side in the loft having been removed to make more space. Also, make sure that vents or a gap have been left around the eaves so that condensation has not had a chance to build up as this can affect the timber work.

- An additional, tall, thin chimney was often built above the kitchen in the corner of the house. These can be precarious and are worth removing if there is additional roofing work being done.

- Walls in the 1920s and 30s usually had a cavity but after eighty years the ties which hold the inner and outer face together can snap, resulting in a bulge in the brickwork which will require attention. It is, principally, the inner wall which carries the load from the floors and roof.

- Look for any signs of cracks in the brickwork as foundations were shallow on many inter-war houses making them vulnerable to ground movement caused by leaky drains, heavy traffic, certain types of clay soil and trees and shrubs being too close to the building.

- With DPCs and cavity walls damp should be less of a problem than with earlier housing. However, the removal of fireplaces, the fitting of double glazing and the blocking of air vents in the walls can cause condensation to build up and areas of mold can appear on the inner face of exterior walls.

- Metal framed windows were very popular in the 1930s and are very strong and durable. Such types of window are worth saving as their Art Deco form and patterned glass are now becoming fashionable. Seals around openings can be replaced, frames repainted and secondary glazing fitted, the latter being more effective than double glazing at reducing noise levels.

- Doors were often a key decorative feature, well worth renovating. You should make sure that the door has three secure hinges, suitable locks and if necessary, discrete bars behind the glazing for extra security. To improve energy efficiency you should seal the gaps around the frame and fit a curtain on a swing rod on its inner face to help keep out drafts. Or you could fit glazed doors across the front of the porch.

- One aspect of Art Deco design which is not so popular at the moment is the original brown and beige, tiled fireplaces which can be found in some properties of this style. These mean hard work to remove and may be a valuable asset sometime in the future so consider either boarding them over (leave a grill or gap, so air can still vent the flue) or use strong colours on an opposing wall to draw attention away from them.